Rum 101: Tulip Science, Truth or Fiction

Arsilica, Inc (creators of the NEAT Glass). is committed to conducting sensory science research on all types of alcohol beverages, including beer, wine, spirits, and lager. Our objective since 2002 has been to provide spirits enthusiasts with a scientifically grounded comprehension of spirits evaluation in order to enhance their enjoyment and appreciation. Our perspective on the consumption of pure, clear spirits from tulips is as follows.

George Manska is the Chief of R&D at Arsilica, and sensory research is my life’s passion. I have a BSME, 60 years of product design experience, including 20 years of sensory research, four sensory patents, and am the author of a published, cited, peer-reviewed research paper on sensory diagnostics in a beverage journal. We object to the assertion that the design of tulip glass is scientifically based by unskilled critics.

Tulip History and Myth: 1700-1800s, a tiny copita (little cup) designed for 22% ABV fortified wines validated cargo in the sherry trade and was nicknamed “dock glass.” Carried back to the UK, eventually copitas (also called tulips) appeared in every household that drank sherry, port, or wine. In the late 1900s scotch sales boom. Since tulips hold a convenient amount of spirit for a single serving, a different costly glass was deemed unnecessary, and wine tulips were enlisted to perform double duty for spirits. The ethanol “nose-cannon” is born, 40% ABV in a 22% ABV designed glass, and the tool is put in place to support expanding scotch popularity. Science is conspicuously absent.

Early 1980s, greedy glass manufacturers twist the International Standards Organization’s official wine tasting ISO-3591 standard, a near exact copy of the copita, renaming it “ISO whisky glass” to sell more glassware. There is no ISO whiskey glass standard. Glencairn introduces a tulip derivative which captures industry and consumer, fueled by spirits marketers, and “nose-cannons” become the norm. Rum and other spirits drinkers borrow them from scotch, and tulip popularity expands. No science here.

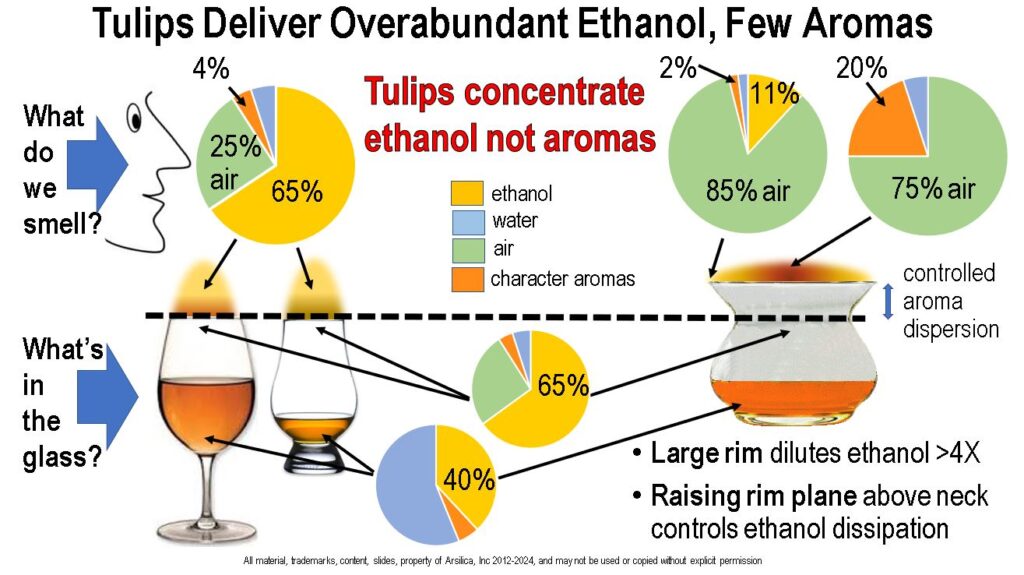

Tulip- the Ethanol Concentrator: Early on, whisky drinkers realize the tiny tulip packs a powerful blast of ethanol, frying nose hairs with concentrated ethanol pungency and interfering with aroma identification. The “nose-cannon,” spurs a search for methods to alleviate pungency. “Fixes” from whisky educators include: (1) inhale through mouth and nose simultaneously, (2) don’t swirl, (3) wafting aromas to the nose adjusts to pungency, and (4) add a little water. These band-aid fixes become the life-blood for tulip justification, augmented by the axiomatic false-science Tiny Rim Doctrine: “Small rims collect all aromas so none can escape detection.”

To the untrained, these “fixes” became “science” because expert marketers, critics and bloggers said so. However, when true scientific principles are applied: (1) simultaneous mouth and nose inhaling reduces the olfactory aroma sample, (2) no swirl = few aromas, (3) wafting acclimates pungency, but can’t prevent ethanol numbing, (4) adding water raises surface tension, shuts down ALL aroma evaporation, not just ethanol. Tiny rims mask aromas which hide behind concentrated, pungent ethanol. All the fixes fail to handle ethanol, the enemy of accurate evaluation. A different glass would have avoided the hoopla. Science dispels myth and disseminates usable knowledge.

The Ethanol Problem: Highly volatile ethanol is medically classified as an anesthetic because it numbs sensory receptor neurons. Drinkers are unaware since numbness occurs painlessly, aided by faulty thinking, “If you can’t see or feel it, it’s not there.” A tulip of 1 ½ oz of 40% ABV rum contains 65% anesthetic ethanol in the headspace The rest is air, water, and 2-4% character aromas. Ethanol raises detection, identification, discrimination thresholds, slows response time, blocks signals to olfactory receptor neurons, and ruins accurate evaluation with distracting pungency. That’s science.

State-of-the Art: For reasons unknown, a scientific approach to glass design was non-existent until 2002 when Arsilica began research. Decades of marketing have ensconced tulips as the popular glass shape for industry and consumer, subconsciously training multiple generations to rely on the presence of pungent, anesthetic ethanol at first sniff to validate a spirit. This sets the stage for high ABV levels (cask strength anyone?) to numb the senses, and hands over purchasing decisions to subliminal and suggestive marketers and vicariously-influential videos. Ethanol’s mental fog is the perfect screen for prurient marketing and bogus claims. Ethanol love and craving has taken priority over distillers’ craft. Tulips create drinkers not evaluators. Marketing-stoked popularity may be fun, but it’s not science.

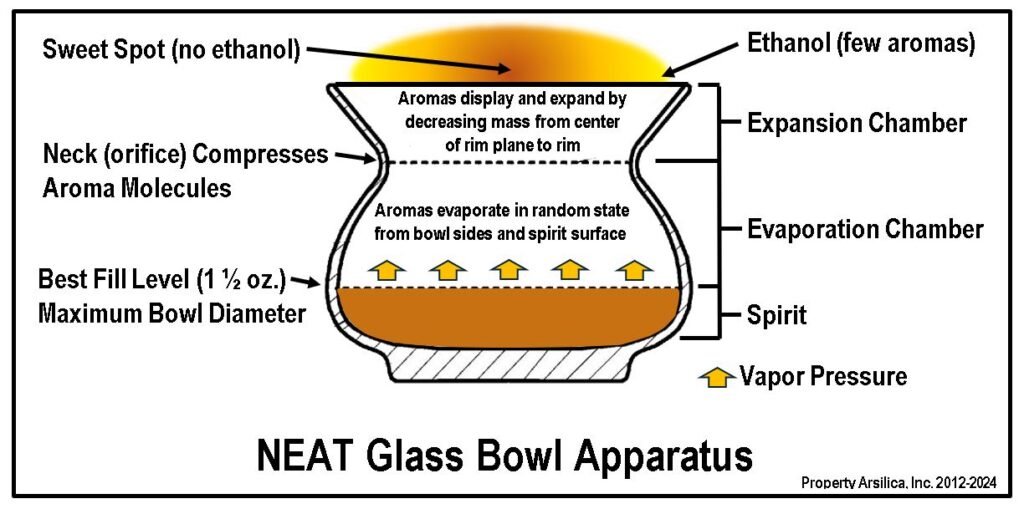

Conclusion: The facts: short, fat, wide-rim glasses and swirling provide more aromas to sniff and can mitigate ethanol for better evaluation, providing a pathway to enjoy aromas for longer than the quickly fading first-sniff memory. A decade of research by Arsilica led to introduction of the sensory engineered NEAT glass in 2012. Other glasses such as wide-mouth tumblers provide some olfactory ethanol relief as well.

Tulips may have topped the marketing game yet scientifically, they fail miserably, working against accurate spirits evaluation. Drinkers encounter a major crossroad on their spiritual journey; (1) stick with the traditional, iconic, unscientific, dysfunctional tulip, or (2) embark on a new experience with a state-of-the-art diagnostic tool. Simply put, you can follow the ethanol-ruled-good-times-party, or discover the spirit. Your glass, your choice.